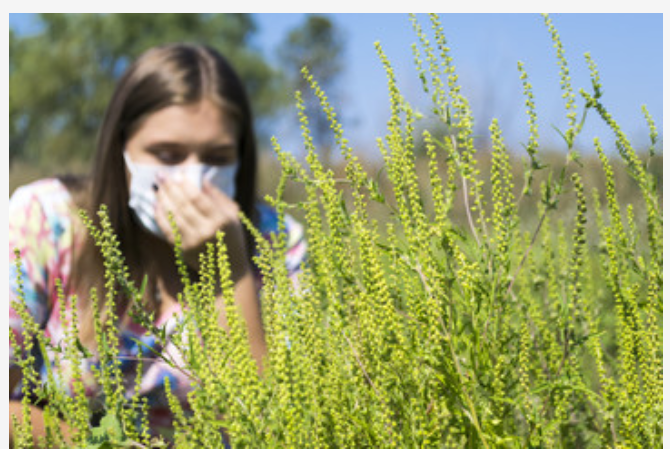

Often, people in the Midwestern United States who suffer from seasonal allergies complain of symptoms in the spring and “in the fall.” However, when asked to specify what part of the fall, they usually mean late August and all of September, not late October when the leaves are on the ground. So, it is more accurate to say “late summer” or “early fall,” when describing this second allergy season of the year. The main allergen responsible for symptoms this time of the year is ragweed. Ragweed is a common weed that grows in many parts of the North America and Central America. Although native to this continent, it has spread to Europe, probably starting in the 1900s during WWI. Unfortunately, for those of us with allergies, it is also a potent allergen.

In Southwest Michigan, ragweed starts to pollinate in mid-August, peaks around Labor Day weekend, and continues till the end of September. There is no detectable ragweed by October 1. As a potent allergen, it is responsible for most of the itchy eyes, running nose, nasal stuffiness and sneezing this time of year. Ragweed pollen levels tend to peak midday and can literally fly for hundreds of miles. So, it doesn’t matter that your yard is a perfectly manicured model of Midwestern grass. You can’t escape ragweed pollen.

Treatment for ragweed is basically the same as for most environmental allergies. The triad of avoidance, medications, and immunotherapy are the hallmark of treatment. Avoidance involves staying indoors, keeping the windows closed, and bathing every night before going to bed (you need to wash that ragweed out of your hair…). I am often asked if there is someplace one could move to avoid ragweed. The short answer is no – unless you’d like to move to Antarctica. However, spending ragweed season on an ocean or large lake (eg. Lake Michigan) shoreline can be helpful. Medications involve allergy eye drops, oral antihistamines, and allergy nasal sprays. Please refer to the previous posts detailing use of OTC allergy medications. Finally, immunotherapy, either via allergy injections or allergy oral drops, probably offers the most effective treatment available.

Michael Park, MD